When Dr Robin Sengupta heard that his friend, Dr Abijit Guha, had been diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia in August, he flew to Guha’s home in Toronto, Canada, to be by his side. The two NRI neurosurgeons had known each other for 20 years, and Guha had helped Sengupta, who resides in the United Kingdom, create the National Neurosciences Centre in Kolkata.

Over the past few months, Sengupta, whom Guha refers to as “Kaku,” has attempted to return the favor. Guha is in need of a bone marrow transplant, but being an only child, does not have access to the preferred sibling donor match. Sengupta contacted Dr N K Mehra, of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, to round up and screen potential donors from the subcontinent, and the worldwide Indian diaspora.

“In practical terms, one-third of those who come have an identical donor in the family,” said Mehra, head of the department of transplant immunology and immunogenetics at AIIMS. “For the remaining two-thirds, we have to look for alternative sources, and so one of the most important sources is from the pool of unrelated voluntary healthy donors.”

It is estimated that at any given time around 50,000 Indians are in need of a bone marrow transplant for ailments from anemia to thalassemia. According to AIIMS oncologist Dr Lalit Kumar, just 2,500 such procedures have been performed in India since 1985. This small figure, according to many of the doctors at the nine Indian hospitals that perform such procedures, relates to a lack of public education, resources, and facilities, and the high cost related to screening donors.

While the Bone Marrow Donors Worldwide registry has over 12.5 million potential donors, 95% are of Caucasian descent, and few are of Indian origin. While doctors found nine potential donors for Guha in that pool, all had either changed addresses or proved mismatched.

Mehra activated a donor drive in Kolkata — because Guha is Bengali, he is more likely to match with other Bengalis — and though his team has screened 143 samples, no donor has been found. Their proposal for a well-funded, multi-centre anonymous donor registry is currently being considered by the Department of Biotechnology. It will “upscale our donor recruitment to nearly 50,000 in the next three-to-five years, and hopefully that will be able to fulfill a portion of our requests,” Mehra said. “Ideally, we should like to have a registry of at least half a million donors.”

But for that effort to succeed, the public must be educated on the bone marrow donation procedure, said Kumar, and relieved of their superstitions. “There are social stigmas there because of lack of awareness — they are scared that their bone marrow may go weak, or they may have problems in the future,” he said.

The education extends to doctors as well, Kumar said. “Many of the physicians in our country think the transplant is the last treatment, and when nothing can be done, the transplant will cure it,” he said. “This is not right — the transplant should be done as part of the treatment.”

Beyond education, doctors face an utter lack of resources and facilities. Around nine centres currently perform the transplants — an ideal number would be 25-30, at least one per state. Meanwhile, those that are currently functioning can be short-staffed, like Dr Mammen Chandy’s unit at Christian Medical College Vellore.

“We have a 10-bed transplant unit, but because we don’t have enough staff, we operate eight beds,” Chandy said. “I have a waiting list for elective transplants for thalassemia patients who have matching donors until June of 2010, because I can only do three transplants per month.”

If the cost per procedure came down, perhaps through increased government funding, more centres performing more transplants could become functional, said Dr N K Ganguly, director general of the Indian Council of Medical Research.

Giving bone marrow like donating blood

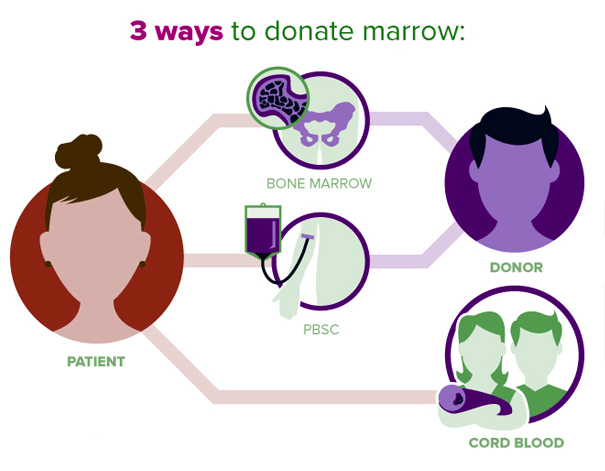

Their proposal for a well-funded, multi-centre anonymous donor registry is currently being considered by the Department of Biotechnology. It will “upscale our donor recruitment to nearly 50,000 in the next three-to-five years, and hopefully that will be able to fulfil a portion of our requests,” Mehra said. “Ideally, we should like to have a registry of at least half a million donors.” But for that effort to succeed, the public must be educated on the bone marrow donation procedure, said Kumar, and relieved of their superstitions. “There are social stigmas there because of lack of awareness they are scared that their bone marrow may go weak, or they may have problems in the future,” he said. But bone marrow regenerates, and the screening test, nowadays, is similar to giving blood. Even the donation procedure, while uncomfortable, does not involve surgical incisions. Rather, doctors use a syringe to extract the marrow from the hip or pelvic bones, after which the donor may feel pain equivalent to a hard fall.

Over the past few months, Sengupta, whom Guha refers to as “Kaku,” has attempted to return the favor. Guha is in need of a bone marrow transplant, but being an only child, does not have access to the preferred sibling donor match. Sengupta contacted Dr N K Mehra, of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, to round up and screen potential donors from the subcontinent, and the worldwide Indian diaspora.

“In practical terms, one-third of those who come have an identical donor in the family,” said Mehra, head of the department of transplant immunology and immunogenetics at AIIMS. “For the remaining two-thirds, we have to look for alternative sources, and so one of the most important sources is from the pool of unrelated voluntary healthy donors.”

It is estimated that at any given time around 50,000 Indians are in need of a bone marrow transplant for ailments from anemia to thalassemia. According to AIIMS oncologist Dr Lalit Kumar, just 2,500 such procedures have been performed in India since 1985. This small figure, according to many of the doctors at the nine Indian hospitals that perform such procedures, relates to a lack of public education, resources, and facilities, and the high cost related to screening donors.

While the Bone Marrow Donors Worldwide registry has over 12.5 million potential donors, 95% are of Caucasian descent, and few are of Indian origin. While doctors found nine potential donors for Guha in that pool, all had either changed addresses or proved mismatched.

Mehra activated a donor drive in Kolkata — because Guha is Bengali, he is more likely to match with other Bengalis — and though his team has screened 143 samples, no donor has been found. Their proposal for a well-funded, multi-centre anonymous donor registry is currently being considered by the Department of Biotechnology. It will “upscale our donor recruitment to nearly 50,000 in the next three-to-five years, and hopefully that will be able to fulfill a portion of our requests,” Mehra said. “Ideally, we should like to have a registry of at least half a million donors.”

But for that effort to succeed, the public must be educated on the bone marrow donation procedure, said Kumar, and relieved of their superstitions. “There are social stigmas there because of lack of awareness — they are scared that their bone marrow may go weak, or they may have problems in the future,” he said.

The education extends to doctors as well, Kumar said. “Many of the physicians in our country think the transplant is the last treatment, and when nothing can be done, the transplant will cure it,” he said. “This is not right — the transplant should be done as part of the treatment.”

Beyond education, doctors face an utter lack of resources and facilities. Around nine centres currently perform the transplants — an ideal number would be 25-30, at least one per state. Meanwhile, those that are currently functioning can be short-staffed, like Dr Mammen Chandy’s unit at Christian Medical College Vellore.

“We have a 10-bed transplant unit, but because we don’t have enough staff, we operate eight beds,” Chandy said. “I have a waiting list for elective transplants for thalassemia patients who have matching donors until June of 2010, because I can only do three transplants per month.”

If the cost per procedure came down, perhaps through increased government funding, more centres performing more transplants could become functional, said Dr N K Ganguly, director general of the Indian Council of Medical Research.

Giving bone marrow like donating blood

Their proposal for a well-funded, multi-centre anonymous donor registry is currently being considered by the Department of Biotechnology. It will “upscale our donor recruitment to nearly 50,000 in the next three-to-five years, and hopefully that will be able to fulfil a portion of our requests,” Mehra said. “Ideally, we should like to have a registry of at least half a million donors.” But for that effort to succeed, the public must be educated on the bone marrow donation procedure, said Kumar, and relieved of their superstitions. “There are social stigmas there because of lack of awareness they are scared that their bone marrow may go weak, or they may have problems in the future,” he said. But bone marrow regenerates, and the screening test, nowadays, is similar to giving blood. Even the donation procedure, while uncomfortable, does not involve surgical incisions. Rather, doctors use a syringe to extract the marrow from the hip or pelvic bones, after which the donor may feel pain equivalent to a hard fall.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteBone Marrow Transplant Cost in India - Bone marrow transplant is known as hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, is a life-saving procedure for patients with various blood disorders, such as leukemia, lymphoma, and aplastic anemia. In India, renowned hospitals and medical centers equipped with cutting-edge infrastructure and advanced medical techniques provide comprehensive care throughout the transplant journey.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteBone Marrow Transplant - Bone marrow transplant is a medical procedure used to treat blood-related diseases like leukemia, lymphoma, and anemia. BMT involves replacing damaged bone marrow with healthy stem cells to restore normal blood cell production. BMT treatment can be life-saving and offers renewed hope for patients battling serious blood and immune disorders. Visit: Best Bone Marrow Transplant Hospitals in India

ReplyDeleteTop Bone Marrow Transplant Specialists in India

Healthcare Tourism Company in India